OTT and CTV are trending, and for good reason. To learn all about OTT and CTV advertising, ways publishers can auction their inventory, and definitions for common terms, here is a complete guide to all things OTT and CTV.

Linear TV refers to traditional television: programming that is delivered by cable, satellite, or broadcasts. Linear TV is scheduled at a particular time on a specific channel. When a viewer tunes in, they land on whatever part of whatever episode, broadcast, or movie is currently airing. To see a specific program, viewers have to tune in at exactly the right time.

Some innovations, like DVR, have allowed viewers some flexibility to adjust program timing, by recording live TV, and fast-forwarding or rewinding.

With Linear TV, one of the key limitations is targeting. Linear programming can only target users based on time of day and ratings.

Plus, for content recorded on DVRs and other devices that allow “time shifting,” viewers are able to fast-forward right through commercial breaks, missing all the ads. This is a major challenge for advertisers.

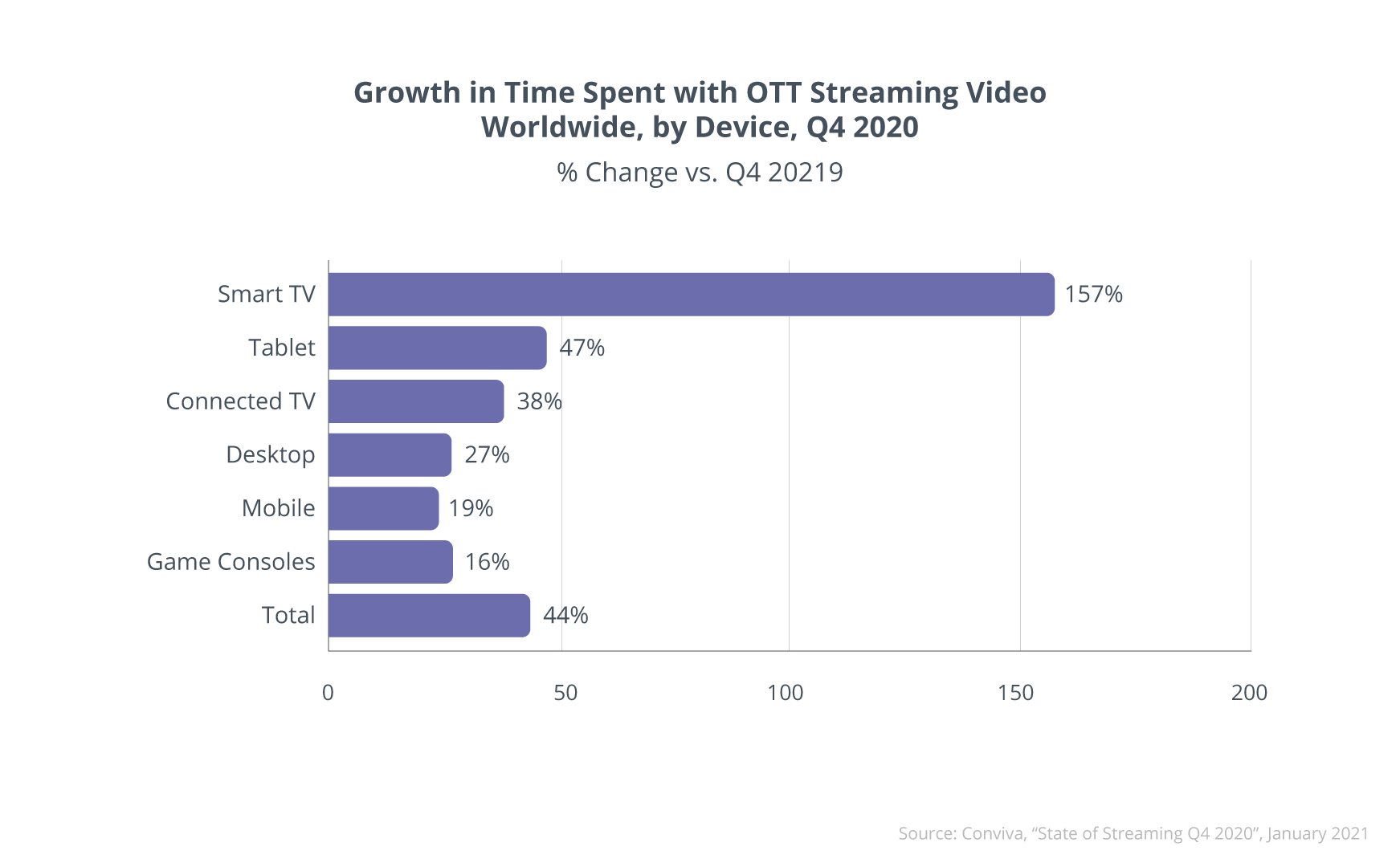

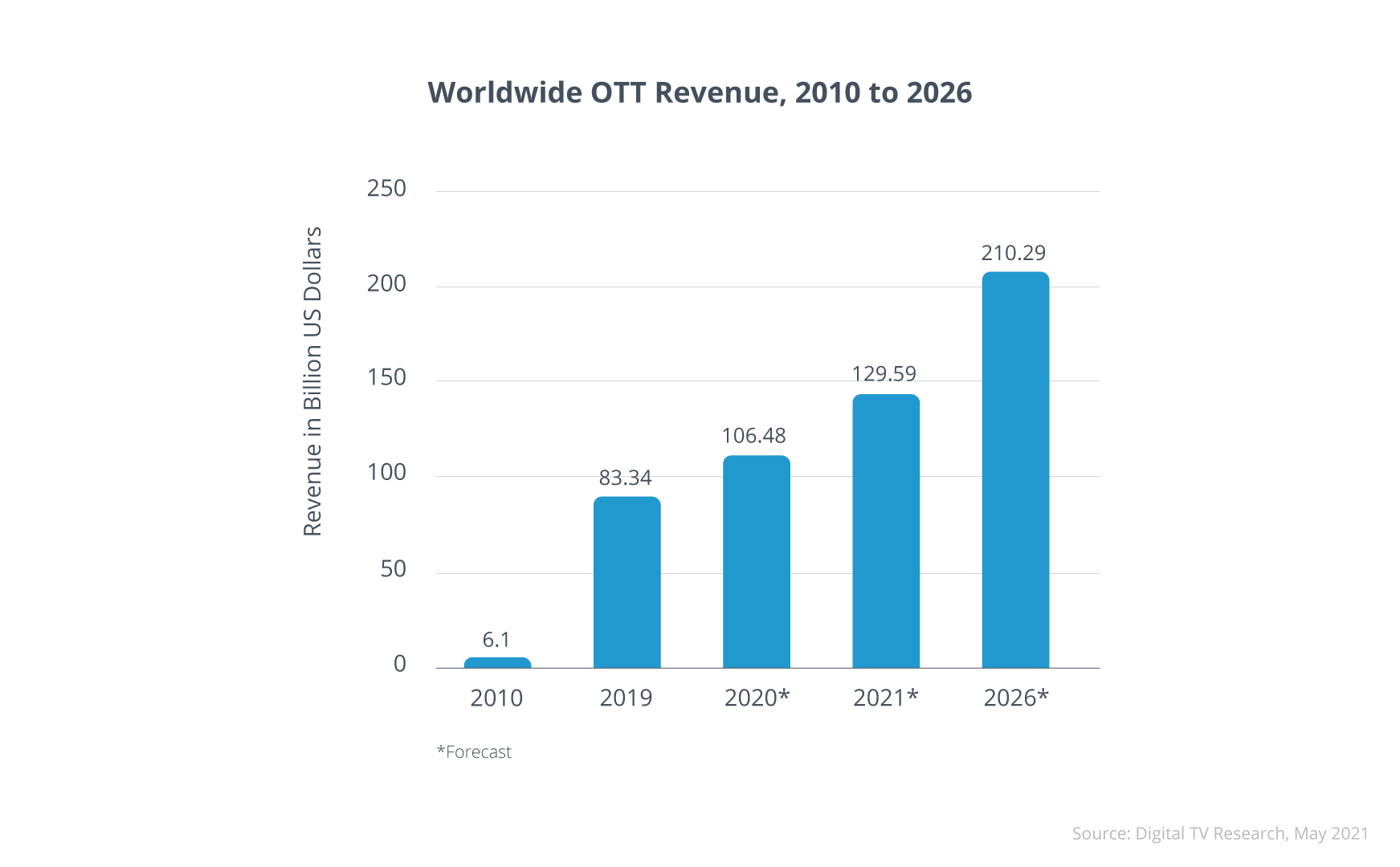

OTT, or “over the top” is video that is streamed over the internet, instead of via satellite, cable, or broadcast. OTT is an overarching category that encompasses any video streaming on the internet including on connected TV devices, mobile devices, computers, tablets, and gaming consoles.

While some OTT and CTV content is streamed live, much of OTT and CTV are available on demand. This means that viewers can stream whatever show or movie they want, and can start at the beginning…or at any second they select.

CTV stands for Connected TV and refers to any TV that streams video via the internet, whether a SmartTV with a built-in internet connection, or a TV that connects separately through streaming sticks or gaming consoles. CTV is a type of over-the-top streaming.

Is it true that CTV is the future of television? According to Leichtman Research Group, 82% of US households own at least one internet-connected TV device. That number keeps growing!

So, why are people cutting the cord, or avoiding it altogether? OTT/CTV video streaming offers ease and quality, and comes with the added convenience of no subscription fees.

The trend towards OTT/CTV was further accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, where strained wallets led to some subscription cutting, and the plethora of high-quality content from OTT/CTV streaming services made the choice an easier one. Viewers didn’t have to give anything up, they just had to switch mediums. They can even connect to their traditional TV with gaming consoles or computer to enjoy CTV content.

OTT/CTV can be supported in a few ways. Through a subscription model, through ads, or through a hybrid approach. There are different types of OTT providers, and each has different advantages.

There are two types of OTT providers and CTV providers: AVOD and SVOD services.

The sheer volume of streaming services also gives viewers infinite choice, but can also add up to a costly monthly bill for internet-subscription services. SVOD, or “subscription-supported video on demand” is very much like its linear TV counterpart. Viewers pay a monthly subscription cost in order to access a library of content (a classic example would be Netflix).

On the other hand, AVOD, or ad-supported video on demand, lets publishers monetize their content with advertisements, while making content free to viewers. Ad-supported video on demand can feel like traditional linear TV advertising, with commercial breaks, and pre-roll, mid-roll, and post-roll advertisements. Viewers tend to like AVOD over SVOD because instead of juggling multiple subscriptions, which can easily rival traditional TV subscription costs, they can watch their content for free, and gain more access to multiple streaming services. As a result, the small gap between AVOD and subscription supported streaming services is rapidly closing, with AVOD gaining in popularity.

Hybrid models include a mix of ad-supported video along with a (lower) subscription fee. An example would be a streaming service that offers a low subscription (or even free subscription) for ad-supported video streaming, but also gives viewers a chance to opt-in to a premium, ad-free subscription for a monthly fee. Some streaming platforms offer their own content ad-free, but play ads during licensed content.

As it turns out, viewers are willing to watch ads in order to access free content. In fact, 63% of video content is consumed as ad-supported video on demand, while 83% of consumers would rather watch AVOD than pay a subscription fee for their video content.[source]

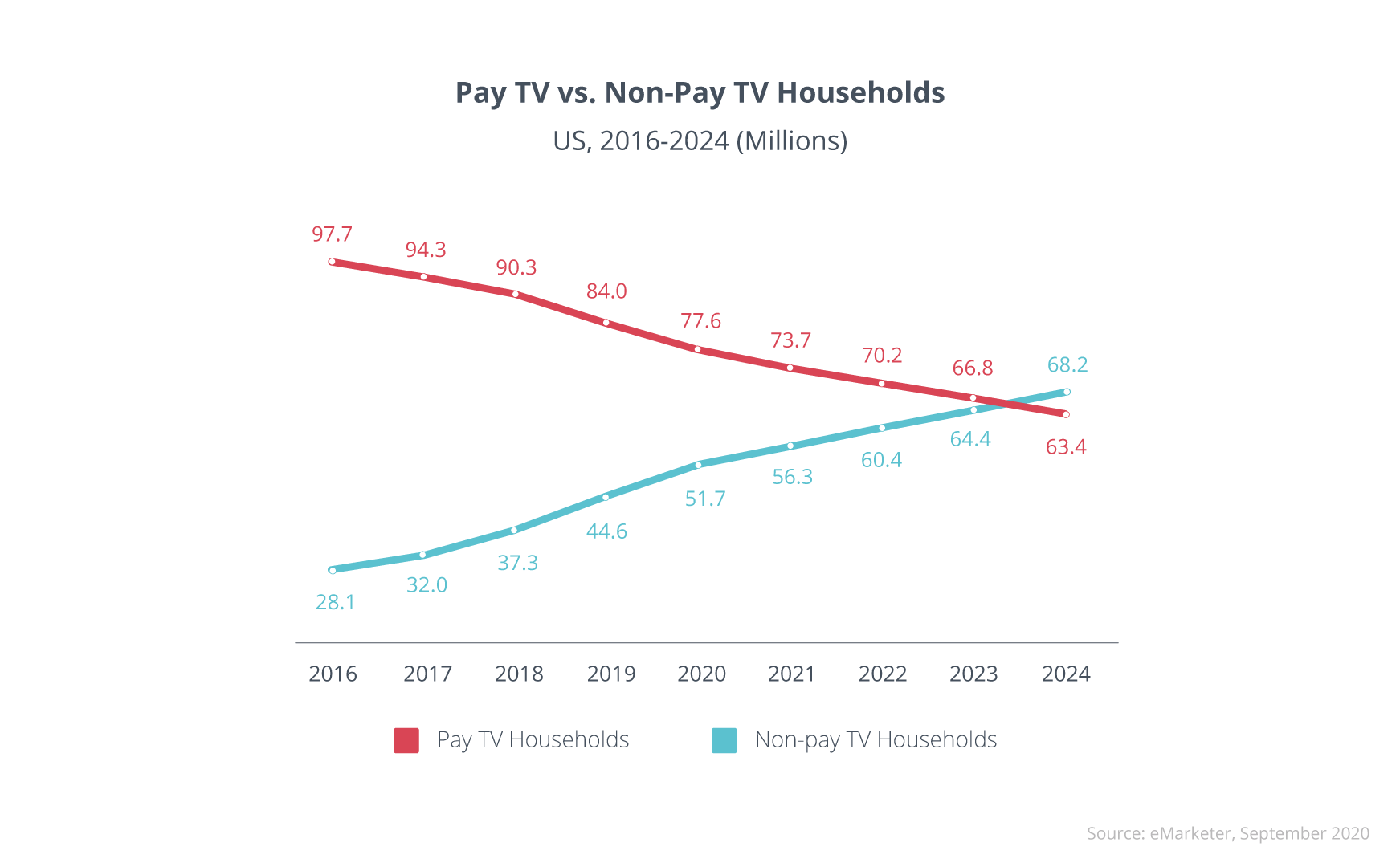

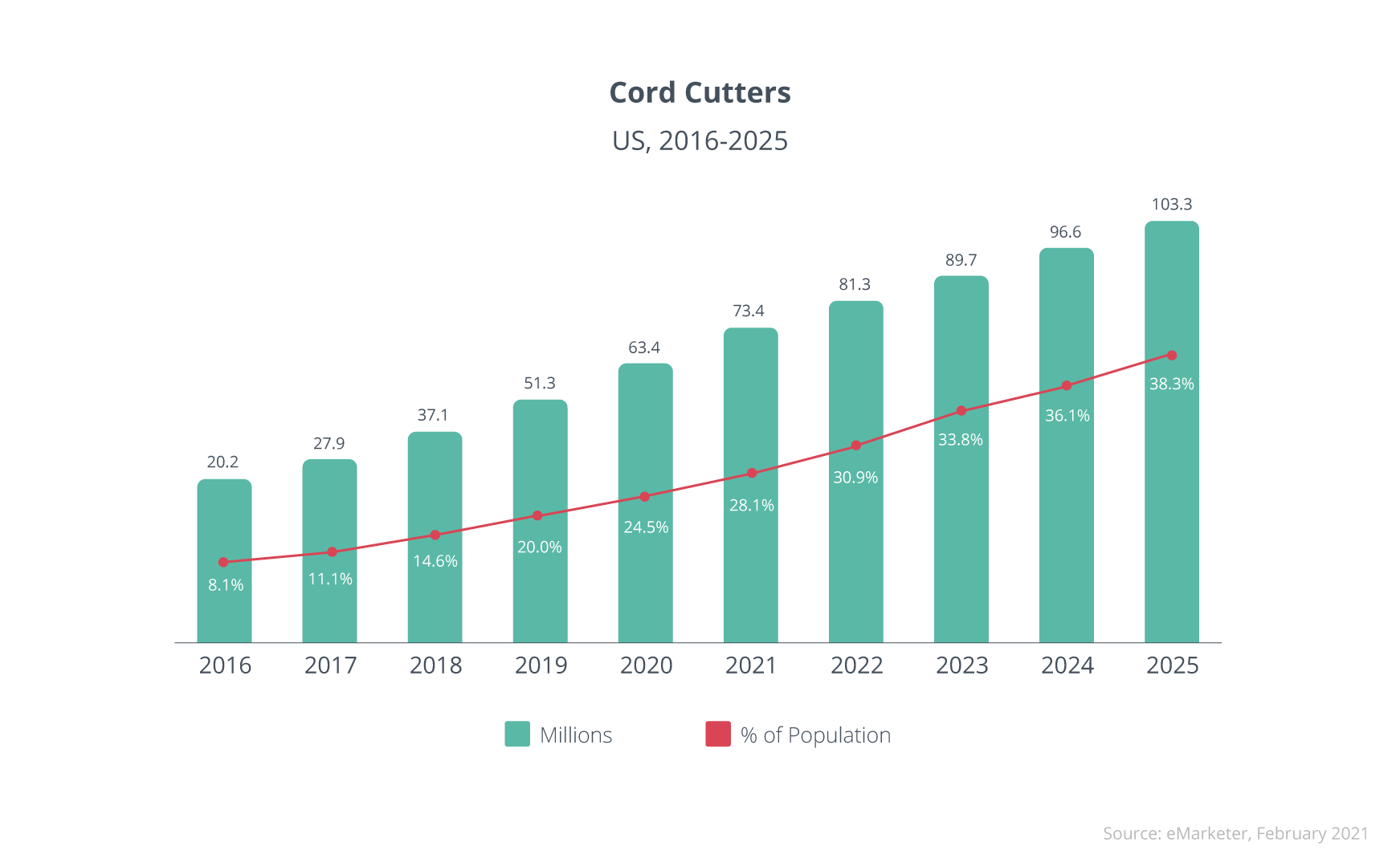

Cord Cutters are viewers who once had a cable TV subscription but have decided to cancel it. Instead of watching traditional TV, they stream video content via the internet on CTV devices or on other OTT platforms.

Cord Nevers are viewers who have never had a traditional TV subscription: they’ve always streamed their content via internet connections. They use AVOD or SVOD content streaming services, instead.

MVPDs (MVPD stands for multichannel video programming distributor) are simply distributors who aggregate content from many providers. More simply, these are major players like Comcast or DISH or DirecTV – these are operators who provide many television channels through one service.

With OTT and CTV, which stream over the internet instead of through cable or satellite connections, there are virtual multichannel video programming distributors. This is sometimes called virtual MVPD or vMPVD. Hulu, for example, is a service that provides nonlinear internet-streaming content (and, like the cable counterpart, offers many different channels to stream along with original programming and content).

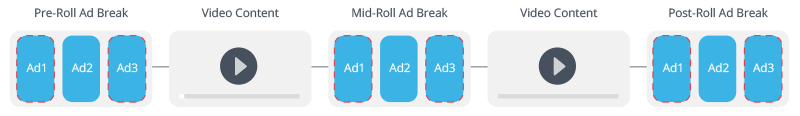

Ad pods are commercial breaks for OTT/CTV inventory. Ad pods are made up of ad slots, and play back to back ads just like traditional television. You can think of an ad pod simply as an ad break.

Ad slots are individual ad placements within an ad pod. They can vary in length. An ad pod is made up of multiple back-to-back ad slots.

Since ad pods are made up of multiple ad slots, publishers have multiple opportunities to monetize their inventory, which increases the value of their ad breaks.

Ad pods and Ad slots are how commercial breaks are made. Where commercial breaks fall in the programming is referred to as pre-roll, mid-roll, and post-roll advertising.

Pre-roll advertising is advertising that plays at the beginning of video content. For OTT and CTV, this means the ad pod that plays at the beginning of the content. The main advantage of pre-roll advertising is that the advertisements play when viewers have just tuned in and are most engaged.

Mid-roll advertising is any advertising that plays throughout the video content, after the show or movie has started.

Post-roll advertisements play at the end of video content. Historically, these tend to be less desirable placements, as viewers aren’t nearly as engaged at the end of their viewing as at the beginning or in the middle.

There are two ways to construct ad pods. Ad pods can be constructed manually, or they can be constructed automatically (sometimes called dynamically).

For manual ad-pod construction, publishers can choose the duration of the ad break and set time requirements for each ad slot.

What is the advantage of manual ad pod construction? With manual ad pod construction, publishers get more control. They get to define the experience for the viewer within the content. Of course, this is a much more laborious process, as publishers set parameters one by one.

For automated ad pod construction (or dynamic ad pod construction), publishers need only select the length of the ad break, and it will be filled accordingly. An OTT/CTV platform partner will fill perfect-length ad pods for publishers based on viewer behavior, available bids, content information, and publisher specifications, so that the optimal ad pod is served to viewers downstream. The advantage to dynamic ad pod construction is that it greatly reduces the manual workload for publishers.

For Video On Demand (VOD) content, ad pods can be constructed manually or dynamically/automatically.

For Live Content, typically ad pods are constructed dynamically. For Live Content, broadcasters set the ad breaks, which define where ad placements will run regardless of platform or streaming service. This gives viewers a consistent experience no matter where they tune in. Ad breaks are defined by SCTE-35 markers.

There are two ways to present ad pods for bidding: by pod or by slot.

Bidding refers to an auction process in which different demand sources compete for inventory. In advertising, this means that marketers and advertisers place bids (offering a price) for publisher inventory (also known as ad placements). The highest bid usually wins.

With per slot bidding, marketers see each slot as a separate request, which means they can bid on any or all of them.

With per pod bidding, marketers are exposed to the entire ad pod and the slots within it. They can bid on more than one slot in an ad pod (though with creative deduplication in place, no more than one will run in the same pod). This creates an opportunity for marketers to bid on specific placement within a pod.

Per pod bidding has many advantages. The key advantage is that because all ad slots are sent in one bid request, per-pod bidding can greatly reduce overhead and costs for marketers, and can also increase eCPMs for publishers. Per-pod bidding reduces Queries per Second (QPS) because instead of sending four separate bid requests for four separate slots, publishers can send a single bid request for an ad pod that contains four slots. This also reduces latency.

Marketers get more transparency for per-pod bidding, because they can see where the different slots fall within a pod. Publishers can set different floor prices for each slot within a pod, based on the value of each slot. While per-pod bidding offers many key advantages, most platforms do not yet offer it.

There are four ways to programmatically auction ad pod inventory. Ad pods can be auction in open auctions, private exchanges, preferred deals, or guaranteed deals.

All marketers on the exchange/SSP/ad network have an opportunity to bid on all available publisher inventory. This is the most traditional form of programmatic auctions. With real time bidding, publishers can set the floor price for an ad, but the marketer demand still determines the final price, and the highest bid wins. Inventory is not guaranteed.

A private exchange is another form of real-time bidding, but instead of being open to all marketers and all publishers, a single publisher invites a mere handful of marketers to participate. To access the auction, these hand-selected marketers will need a time sensitive deal ID. Publishers set a floor price, and the bidding starts there. As in the open auction, the highest bid wins. Inventory is not guaranteed.

A Preferred Deal is a private, 1:1 relationship between a publisher and a marketer, offering “first dibs” on premium ad space. The publisher offers premium inventory to the marketer at a pre-negotiated fixed eCPM price. When an ad request comes through, a marketer with a preferred deal has an opportunity to bid at the pre-negotiated fixed eCPM price in real time, before the inventory heads to open auction. Inventory is not guaranteed.

With a guaranteed buy, a publisher offers specific, reserved inventory to a marketer at a fixed price. Publishers and marketers negotiate a price for a guaranteed volume of impressions, or flight date. This is similar to a direct sale/buy, but programmatic automation replaces the manual IO process, improving efficiency and reducing error. In addition to these four programmatic auction types, programmatic header bidding for CTV can help publishers maximize revenue while giving marketers more opportunities to bid.

What is header bidding? Header bidding is a real-time pre-auction that enables multiple ad exchanges to bid on the same inventory simultaneously. The highest bid wins. As an alternative to the traditional waterfall, header bidding creates a level bidding playing field, while improving demand (and eCPMs) for publishers. Ad pod header bidding is simply header bidding for ad pods. This means that all the advantages of header bidding are available for ad pods, as well.

So, how do ads get inserted into commercial breaks for ad-supported content (both live and on demand)? This can be done one of two ways: on the server side, or on the client side.

Client-Side Ad Insertion (CSAI) vs. Server-Side Ad Insertion (SSAI)/Dynamic Ad Insertion (DAI)

Client-side ad insertion means that publishers have to request ads themselves based on specific markers. Basically, this means that the video player will make a call to a server to request the ad when the marker appears. The ad gets called and delivered in a wrapper.

Client-side ad insertion has many disadvantages. First of all, it requires a lot of heavy lifting from the publisher. Additionally, there is a lot of latency, which translates to a poor viewer experience. On top of this, because ads are called in as the placement becomes available, the ad quality may not match the video quality. This can be very jarring. If the ad quality is even better than the content, it can also cause buffering, frustrating viewers.

SSAI stands for server-side ad insertion, and is often used interchangeably with Dynamic Ad Insertion, or DAI. SSAI and DAI describe the process of stitching ads into content.

Server-Side Ad Insertion means that ads are pre-stitched into content. As a result, these ads match video streaming quality, lower latency, reduce buffering, and deliver a smooth viewer experience. Ad content can also be contextually aligned to video content to deliver a hyper-relevant viewer experience.

For live content, some platforms (like Smaato’s) can dynamically stitch in ad pods based on SCTE marker restrictions. That means that for live content, publishers and marketers get the same in-house SSAI/DAI benefits that they do for video on demand (VOD) ad insertion.

The main disadvantage of Server-Side Ad Insertion (SSAI) is the high risk of ad fraud. On top of this, publishers often have to pay a third party for SSAI services. Bad actors reach out to ad servers, pretending to stitch ads on behalf of reputable, real publishers. The server can be tricked into delivering ads to the fraudster, who then confirms that the ads were “viewed.” In the end, they pocket the advertiser’s money without delivering the ad to the end user.

At Smaato, we have eliminated this risk by completing all of our SSAI services in-house, without the use of a third party vendor. This also saves publishers money.